The Black Panther Party: The Rise and Fall of a Revolutionary Movement

By Darius Spearman (africanelements) | June 2, 2024

Support African Elements at patreon.com/africanelements and hear recent news in a continuous playlist. Additionally, you can gain early access to ad-free video content.

INTRODUCTION

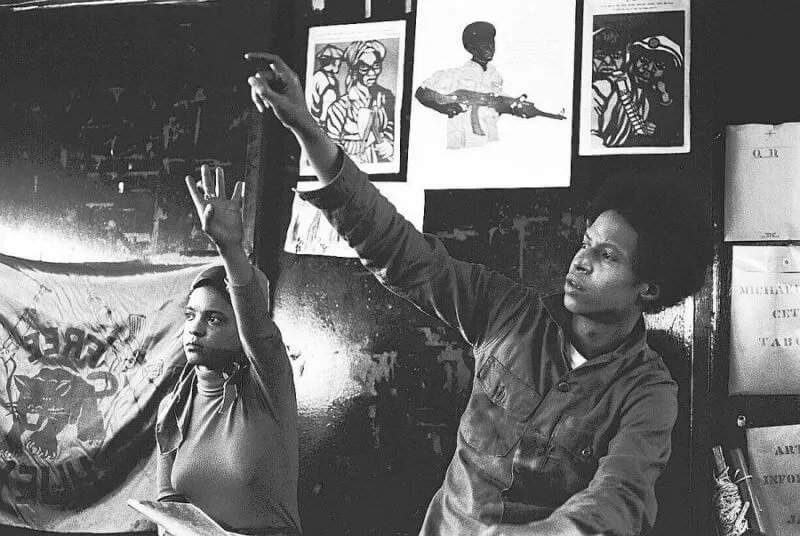

When speaking of the Black Panther Party, black leather jackets, berets, and guns often come to mind. However, the Black Panther Party was much more than that. This article will explore some lesser-known aspects of the Black Panther Party, its revolutionary ideology, and the vulnerabilities that led to its demise.

WHAT IS “REVOLUTIONARY BLACK NATIONALISM?”

In October 1966, six black men (Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, Elbert “Big Man” Howard, Sherwin Forte, Reggie Forte, and “Little” Bobby Hutton) founded the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. They founded the organization on principles of Revolutionary Black Nationalism. To understand what that means, it is essential first to explore what Black Nationalism is. Black Nationalism is an ideology that promotes racial solidarity among Black People and advocates for Black self-determination and political power within the United States.

[I]n its simplest form, Black Nationalism is the recognition of cultural and racial commonality and a call to racial solidarity. …The political objectives of Black Nationalism can range from the admonition that black people must control the politics and economics of their communities, to the creation of a separate black nation in North America or returning to the African home land. (Harris 162)

Many expressions of Black Nationalism include Black Cultural Nationalism, which celebrates the African origins of Black culture, and immigrationism, which emphasizes a physical return to the continent of Africa. As a revolutionary Black Nationalist organization, the Black Panther Party embraced anti-colonialism and saw themselves as part of the global movement against colonization, racism, and capitalism. They believed that Africa and all colonized people had a right to self-determination and supported Pan-Africanism. Pan-Africanism is a worldview that advocates for global solidarity amongst Black people throughout the global diaspora. The Black Panther Party saw itself in kinship with colonized people worldwide who were oppressed and exploited economically and politically. Like colonized people, the Black Panthers saw the police as a colonial occupying force and as agents of their economic and political oppression.

REVOLUTIONARY BLACK NATIONALISM

The Black Panther Party gained inspiration from Malcolm X, whom Marcus Garvey influenced. Nevertheless, the Black Panthers departed from both Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey, who tended to emphasize the development of Black business and entrepreneurship as the path to prosperity in the Black community. Instead, the Black Panthers embraced Revolutionary Black Nationalism, which heavily emphasized collectivism and people power to meet the community’s needs. Revolutionary Black Nationalism is an ideology that combines elements of both Black Power and revolutionary socialism.

Revolutionary Nationalists maintain that African-Americans can not achieve liberation in the United States within the existing political and economic system. Therefore, they call for revolution to rid the society of capitalism, imperialism, racism, and sexism. (Harris 163)

The Black Panther Party required of its members an astute understanding of revolutionary theory and practice. Weekly mandatory political education included readings from Frantz Fanon, Paulo Freire, Ernesto “Che” Guevarra, Karl Marx, and Mao Tse Tung’s Little Red Book. Putting theory into practice, the Black Panther Party had dozens of community programs ranging from the Breakfast for Children program to community health clinics – all free to community members.

The Black Panther Party’s original Ten Point Program, first publicized in May 1967, read: “WHAT WE WANT NOW!”

- We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black community.

- We want full employment for our people.

- We want an end to the robbery by the White man of our Black community.

- We want decent housing, fit for shelter [of] human beings.

- We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present day society.

- We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

- We want an immediate end to police brutality and murder of Black people.

- We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county, and city prisons and jails.

- We want all Black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black communities.

As defined by the constitution of the United States. - We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace.

The Black Panthers elaborated on their ten-point program and the revolutionary politics that underlies it in an additional section entitled, “WHAT WE BELIEVE….” (Bloom 70-72)

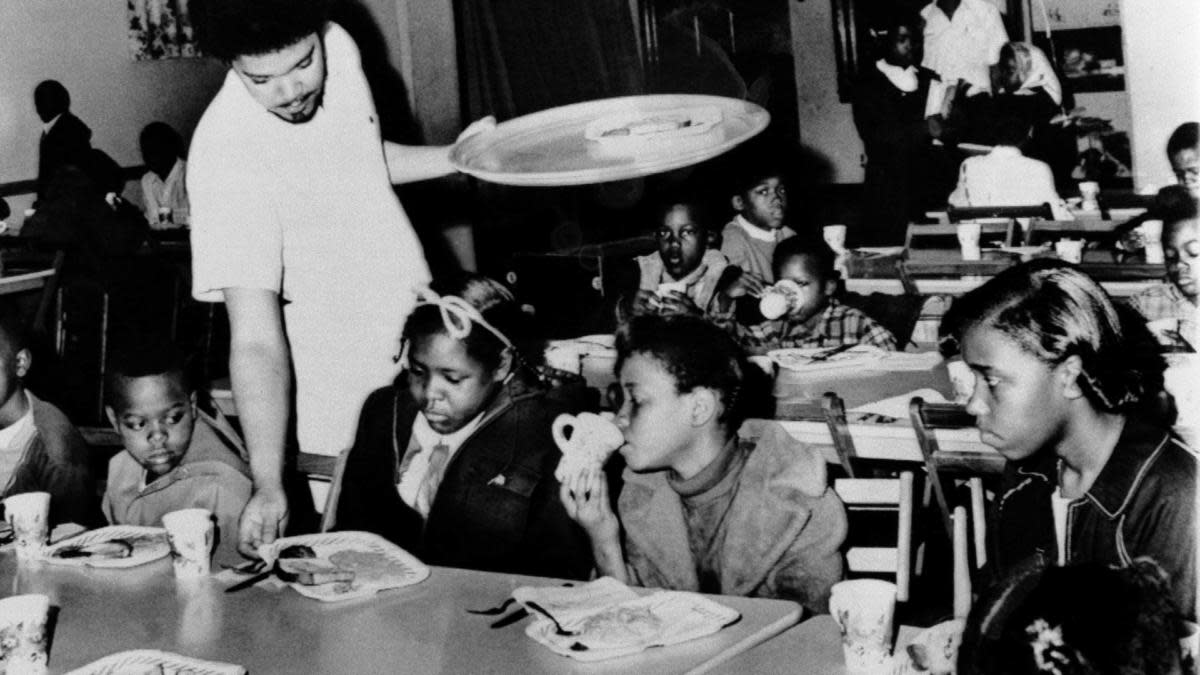

SURVIVAL PROGRAMS

The Black Panther Party instituted many programs within the community to further their plan. Many familiar with the Black Panthers are aware of their police patrol. As Elbert “Big Man” Howard explains,

We would get in our cars and ride around until we saw the police stop somebody. We would get out with our guns and stand at the legal distance and observe these so-called officers of the law in performance of their duty. Of course, they didn’t like that. …

And then we would tell the person that’s been accosted by the police, go ahead and take the arrest. Don’t resist. We are going to follow you down to the jail and we are going to bail you out. (Guest Lecture: Elbert ‘Big Man’ Howard)

While the Panthers were best known for their confrontations with police, they are less well known for their community programs. By some accounts, there were over 200 of these “survival programs” that the Panthers administered. A small list of these programs included free breakfast for children, community health clinics, child care, a program directly addressing sickle cell anemia, dental and optometry programs, pest control, a food program that gave out 5000 bags of groceries per week, free clothing and shoes, and free transportation for prison visitations. (Survival Programs) Additionally, the Panthers instituted seniors against a fearful environment (SAFE ), as “Big Man” explains:

When senior citizens got their checks on the first of the month and needed to go to the doctor when needed to go to the bank or whatever, they were set upon by predators who would take their money and abuse them. So, we set up a program where we would drive them or escort them wherever they needed to go and with the Panthers guiding them they were not set upon by anybody. Because they know that they had some problems coming if they did. (Guest Lecture: Elbert ‘Big Man’ Howard)

LIMITATIONS

Like the ideology of Civil Rights that W. E. B. DuBois put forward and the ideology of separatism and self-determination that Booker T. Washington espoused, the Black Panther Party and its expression of Revolutionary Black Nationalism came with its complement of strengths and limitations. Many of its critics have denounced the Panthers as a criminal organization. Their denunciation is a distortion of the truth. As a radical revolutionary organization, the Panthers reached out to all oppressed people — including gang members and incarcerated people. As part of an intentional outreach, the Black Panthers in Chicago, for example, attempted to forge a coalition with the Blackstone Rangers, a Chicago gang. Howard Saffold, who was then a member of Chicago’s Afro-American Patrolmen’s League, recalls:

The Panthers were pursuing an ideology that said we need to take these young minds, this young energy, and turn it into part of our movement in terms of black liberation and the rest of it. And I saw a very purposeful, intentional effort on the part of the police department to keep that head from hooking up to that body.(“American Experience. Eyes on the Prize.Transcript”)

Because their vision of Revolutionary Nationalism included Marxist elements during a climate of intense Cold War anti-communism, the Black Panther Party found itself at the center of a federal counterintelligence program (COINTELPRO). COINTELPRO was an FBI program that ran between 1956 and 1971. Its purpose was to disrupt domestic political organizations deemed subversive to the United States government. In 1968, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover called the Panthers “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country.” (“Hoover Calls Panthers Top Threat to Security”) To disrupt the organization and sow conflict between the Panthers and other groups, Hoover directed his field offices to “exploit all avenues of creating further dissension” and to submit regular reports on “imaginative and hard-hitting counterintelligence measures aimed at crippling the BPP.” (Hoban)

In doing so, FBI agents in Chicago

wrote an anonymous letter to Jeff Fort, the leader of the Blackstone Rangers warning Fort that the Panthers have, “a hit out for you.” The Bureau knew that the information was false, but believed that Fort might take retaliatory action against the Panthers. (“American Experience. Eyes on the Prize.Transcript”)

That the Black Panther Party deliberately reached out to the formerly incarcerated exposed them to another vulnerability. The Panthers recognized the difficulty that having a criminal record imposed on one’s ability to gain employment or even find a place to live. As such, they deliberately sought to create a meaningful space for ex-offenders in their many community service programs. Unfortunately, those are the very people most vulnerable to police coercion. FBI informant William O’Neal recalls:

My recruitment by the FBI was very efficient, very simple, really. I’d stole a car and went joyriding over the state limit. And they had a potential case against me, and I was looking for an opportunity to work it off. And a couple months after, that opportunity came when the FBI agent Roy Mitchell asked me to go down to the local office of the Black Panther Party and try to gain membership. (“American Experience.Eyes on the Prize.Transcript”)

CONCLUSION

The Black Panther Party took a Revolutionary Black Nationalist platform and applied it to a comprehensive, creative, and energetic program. They were committed to learning from global anti-colonial movements and applying those principles at the community level. Nevertheless, their vulnerabilities, combined with state repression, led to internal friction and a culture of mistrust that eroded the organization from the inside out. As a result, the Black Panther Party officially disbanded in 1982. What lessons can we learn from those vulnerabilities? Could the demise of the Black Panther Party have been avoided?

About the author

Darius Spearman has been a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College since 2007. He has authored several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890. You can visit Darius online at africanelements.org.

SOURCES

“American Experience.Eyes on the Prize.Transcript.” American Experience.Eyes on the Prize.Transcript | PBS, 23 August 2006, http://www.shoppbs.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/eyesontheprize/about/pt_206.html. Accessed 9 June 2022.

“Hoover Calls Panthers Top Threat to Security.” ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/docview/147638465. Accessed 9 June 2022.

Survival Programs, http://www.itsabouttimebpp.com/Survival_Programs/survival_programs_index.html

“Guest Lecture: Elbert ‘Big Man’ Howard (June 7, 2015).” African Elements, 26 May 2021, www.africanelements.org/admindarius/guest-lecture-elbert-big-man-howard-june-7-2015/.

Bloom, Joshua, and Waldo E. Martin. Black against Empire: the History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. University of California Press, 2016.

Harris, Jessica Christina. “Revolutionary Black Nationalism: The Black Panther Party.” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 85, no. 3, 2000, pp. 162–74. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2649073. Accessed 7 Jun. 2022.

Hoban, Virgie. “’Discredit, disrupt, and destroy’: FBI records acquired by the Library reveal violent surveillance of Black leaders, civil rights organizations.” UC Berkeley Library News, 18 January 2021, https://news.lib.berkeley.edu/fbi. Accessed 9 June 2022.