Support African Elements via Patreon; https://www.patreon.com/africanelements

*Ad Free Videos for as little as $1/Month Subscription!!*

The Seminole Wars: A Crucible for Black and Indigenous Relations

Unveiling the Seminole Wars, where Black and Indigenous bonds forged a legacy of resistance and unity in the face of adversity.

By Darius Spearman (africanelements)

About the author: Darius Spearman is a professor of Black Studies at San Diego City College. He has been an educator since 2007 and is the author of several books, including Between The Color Lines: A History of African Americans on the California Frontier Through 1890.

Introduction: The Seminole Wars as a Meeting Ground

The Seminole Wars were more than just military skirmishes; they were a crucible for the complex relationships between Black and Indigenous communities. These wars, fought over three main periods—1817-18, 1835-42, and 1855-58—were as much about Black freedom as they were about Indigenous sovereignty. So, let’s dive deeper into this intricate tapestry of alliances, betrayals, and survival.

In the vast and mysterious landscapes of 18th-century Florida, where swamps and untamed wilderness dominated, the story of the Seminole and African Americans began to unfold. The Seminole, a Native American people with roots in the Creek Confederacy, derived their name from the Creek word ‘simanó-li’. Intriguingly, this term might trace its origins to the Spanish word ‘cimarrón’, evoking images of the ‘wild’ or the ‘runaway’. This notion of ‘running away‘ becomes emblematic in the intertwined destinies of the Seminole and African Americans.

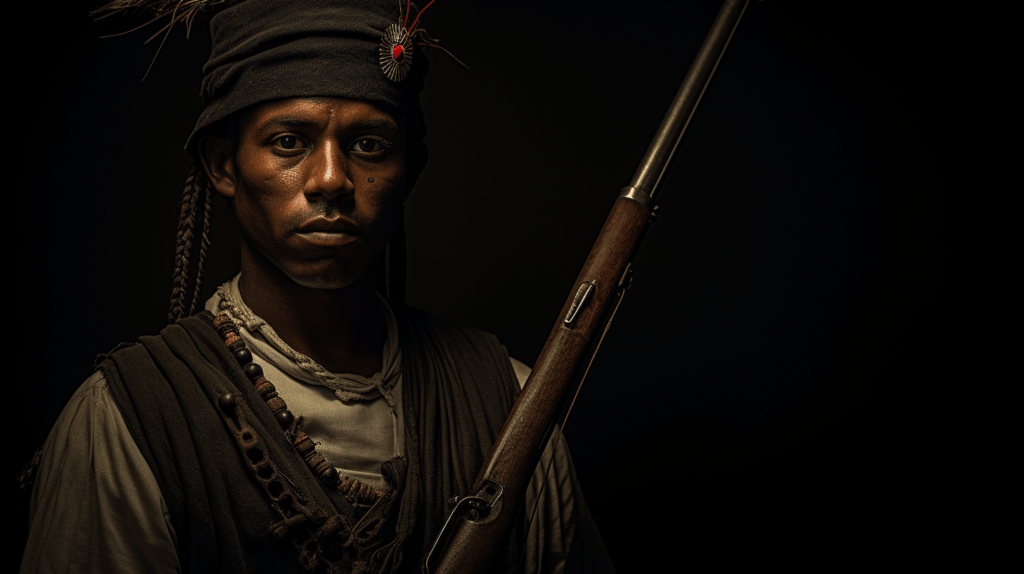

During this period, many African slaves, driven by a yearning for freedom and a life unshackled, ventured into Florida’s depths. Their quest for liberty led them to the Seminole. These escaped individuals, soon to be recognized as the Black Seminoles or Seminole Maroons, found more than just sanctuary among the Seminole; they discovered a sense of belonging. As the years passed, they not only established vibrant communities but also interwove their destinies with the Seminole through marriage and shared traditions, becoming an integral thread in the Seminole’s rich cultural fabric.

However, this narrative is not merely one of cultural amalgamation. It is a testament to resistance and unity. The Seminole and Black Seminoles, bound by mutual respect and shared challenges, stood united against European-American advances and valiantly resisted U.S. forces in the Seminole Wars. Their alliance, born out of shared adversities and a collective determination to defend their territories and heritage, showcases the profound impact of collaboration and solidarity.

In reflecting upon the relationship between the Seminole and Black Seminoles, one is reminded of the enduring power of unity, the resilience that emerges from diverse groups converging, and the indomitable spirit of resistance. Their shared history is not a mere chapter in the annals of the past but a luminous beacon highlighting the human capacity for collaboration, perseverance, and hope.

The Seminole Wars: A Brief Overview

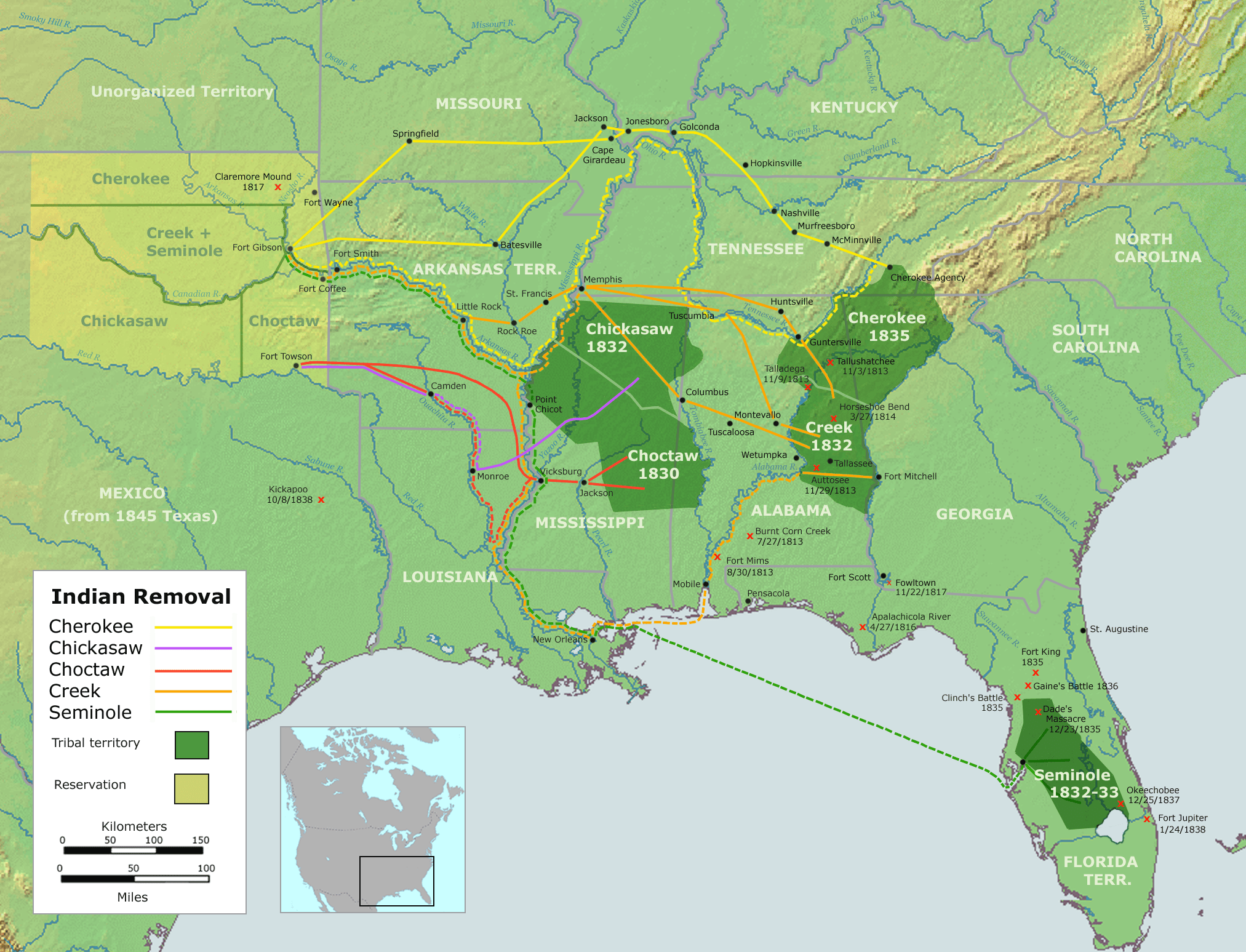

The Seminole Wars were a series of conflicts between the United States and the Seminole people in Florida. The first war (1817–18) began as an attempt by U.S. authorities to recapture runaway Black slaves living among the Seminoles. The second war (1835–42) was sparked by the refusal of most Seminoles to leave their reservation north of Lake Okeechobee. The third war (1855–58) was a renewed effort to remove the remaining Seminoles from Florida.

| War | Years | Main Trigger | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Seminole War | 1817-1818 | Recapture of runaway slaves | Spain cedes Florida to the U.S. |

| Second Seminole War | 1835-1842 | Indian Removal Act | Most Seminoles removed to the West |

| Third Seminole War | 1855-1858 | Final removal of Seminoles | Paid exodus of remaining Seminoles |

Why Should We Care?

- The Complexity of Alliances: How did the Seminole Wars shape the alliances between Black and Indigenous people?

- The Fight for Land and Freedom: What role did these wars play in the broader struggles for Indigenous land rights and Black freedom?

- The Legacy Today: How do the Seminole Wars continue to impact Black and Indigenous communities today?

The First Seminole War: The Quest for Black Freedom

Runaway Slaves and Seminole Alliances

The First Seminole War was ignited by the U.S. government’s attempts to recapture runaway Black slaves who had found refuge among the Seminole bands. These Black runaways, often referred to as Black Seminoles, formed alliances with the Seminole people. According to Kwame Dixon, these alliances were not just strategic but also cultural, leading to a unique “Black Seminole Ethnogenesis” (Dixon 8-24).

“The Black Seminoles were not merely runaway slaves but had formed a unique cultural identity that was a fusion of African and Seminole elements.”

(Dixon 12)

The Cultural Fusion: More Than Just Allies

The Black Seminoles didn’t just live among the Seminoles; they became part of the community. They adopted Seminole clothing, participated in their ceremonies, and even married into the tribe. This wasn’t just a marriage of convenience but a genuine cultural fusion. Dixon elaborates on this by discussing the shared rituals and languages that emerged within these communities (Dixon 15-18).

The First Seminole War (1817-1818)

The Fugitive Slave Act: A Legal Nightmare

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was a legal tool used by slave owners to recapture runaway slaves. This act became a significant concern for the Black Seminoles. They weren’t just fighting the Seminoles’ battles; they were fighting for their own freedom. The act allowed slave owners to cross state lines to recapture slaves, making the Black Seminoles’ position even more precarious.

“The Fugitive Slave Act was not just a legal document but a death sentence for many Black Seminoles.”

(Prucha 427-450)

The Role of General Andrew Jackson

General Andrew Jackson led the U.S. military forces in invading Seminole territory. His forces scattered the villagers, burned their towns, and even seized Spanish-held Pensacola and St. Marks. This aggressive action led Spain to cede its Florida territory under the Transcontinental Treaty in 1819. But what did this mean for the Black Seminoles? It meant a betrayal of their newfound freedom and a return to the shackles of slavery.

Jackson’s Motivations: More Than Just Land

Jackson’s invasion wasn’t just about claiming land; it was about asserting American dominance and control. This was a message to both the Seminoles and the Black Seminoles that their freedom and sovereignty were threats to the American project. Jackson’s actions were not just military but ideological, aimed at quashing any form of resistance to American expansionism.

“Jackson’s invasion was not just an attack on the Seminoles but a direct assault on the freedom of the Black Seminoles”.

(Prucha 427-450).

The Aftermath: Broken Alliances and Shattered Dreams

The First Seminole War ended with the U.S. gaining control of Florida, but at a high cost. The Seminoles were pushed further south into the Florida peninsula, and many Black Seminoles were recaptured and returned to slavery. This was a devastating blow to the Black Seminoles, who had tasted freedom and formed alliances that they thought would last. The war shattered these dreams, but also sowed the seeds for future resistance.

“The First Seminole War may have ended, but the struggle for freedom and alliances was far from over.”

(Porter 390-421)

The Second Seminole War: The Struggle for Land and Identity (1835-1842)

The Indian Removal Act: A Policy of Displacement

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was a policy initiated by President Andrew Jackson to relocate Native American tribes living in the southeastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River. This policy was the main trigger for the Second Seminole War. The Seminoles, including the Black Seminoles, were opposed to removal. They had already lost their lands once; they weren’t willing to lose them again.

The Treaty of Payne’s Landing: A Controversial Agreement

In 1832, a few Seminole chiefs signed the Treaty of Payne’s Landing, agreeing to move west if the lands were suitable. However, this treaty was highly controversial. Many Seminoles, including Osceola, a prominent leader, opposed it. They argued that those who signed the treaty did not represent the Seminole nation. This internal division further complicated the Seminole stance against removal.

“The Treaty of Payne’s Landing was a divisive issue among the Seminoles, leading to internal conflicts and disagreements.”

(Mahon 65-68)

The Role of Osceola: A Symbol of Resistance

Osceola, a young Seminole leader, became a symbol of resistance against removal. He rejected the Treaty of Payne’s Landing and led a faction of Seminoles against U.S. troops. Osceola’s resistance made him a hero among the Seminoles and the Black Seminoles. His capture and death in 1838 were a significant blow to the Seminole resistance but also turned him into a martyr for the cause.

“Osceola was not just a leader but a symbol of Seminole resistance against American expansionism.”

(Weisman 198-212)

Black Seminoles in the Second Seminole War

The Black Seminoles played a crucial role in the Second Seminole War. They were skilled woodsmen, excellent marksmen, and knew the Florida terrain well. They served as scouts, spies, and even led Seminole bands in battle. Their involvement was not just about aiding the Seminoles but also about securing their own freedom.

John Horse: A Black Seminole Leader

One of the most prominent Black Seminole leaders was John Horse, also known as Juan Caballo. He was a skilled military strategist and a charismatic leader. John Horse led Black Seminole warriors in several key battles, including the Battle of Lake Okeechobee. His leadership was crucial in sustaining the Seminole resistance and keeping the dream of freedom alive for the Black Seminoles.

“John Horse was a formidable leader whose military skills were matched only by his commitment to the freedom of the Black Seminoles.”

(Porter 390-421)

The Dilemma of Freedom: The Role of Slavery in the War

The issue of slavery was a significant factor in the Second Seminole War. The U.S. government was not just fighting to remove the Seminoles but also to reclaim runaway slaves. This made the Black Seminoles valuable allies but also targets. Their freedom was a direct challenge to the institution of slavery, making them a threat that needed to be eliminated.

“The freedom of the Black Seminoles was not just a Seminole issue but a challenge to the very institution of slavery.”

(Prucha 427-450)

The End of the Second Seminole War: A Pyrrhic Victory

The Second Seminole War ended in 1842, but it was a Pyrrhic victory for the U.S. government. Most of the Seminoles, including the Black Seminoles, were removed to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). However, a small number remained in Florida, living in the Everglades. The war was costly in terms of lives and resources, and it left a lasting impact on the Seminole and Black Seminole communities.

“The Second Seminole War may have ended, but its impact was long-lasting, shaping the future of the Seminole and Black Seminole communities for generations to come.”

(Mahon 65-68)

The Third Seminole War: The Final Chapter (1855-1858)

The Spark: Renewed Efforts for Removal

The Third Seminole War (1855–1858) was sparked by renewed efforts to remove the remaining Seminoles from Florida. Tensions had been simmering for years, and the discovery of gold in California further fueled the desire for Seminole lands. The U.S. government was determined to remove the last remnants of the Seminole Nation, including the Black Seminoles, once and for all.

The Billy Bowlegs War: A Last Stand

The Third Seminole War is often referred to as the Billy Bowlegs War, named after the Seminole leader who led the resistance. Billy Bowlegs and his band were among the last holdouts, refusing to leave their ancestral lands. This war was not just about land but also about preserving a way of life for both the Seminoles and the Black Seminoles.

“The Third Seminole War was the final chapter in a long struggle for land, identity, and freedom.”

(Weisman 198-212)

The Role of the Black Seminoles: A Continued Struggle for Freedom

The Black Seminoles continued to play a crucial role in the Third Seminole War. They were not willing to give up their freedom without a fight. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, they fought alongside the Seminoles, sharing the risks and the consequences. Their involvement was a testament to their resilience and their unyielding quest for freedom.

“The Black Seminoles were not bystanders in the Third Seminole War; they were active participants fighting for their freedom.”

(Porter 390-421)

The End of the Third Seminole War: An Uncertain Future

The Third Seminole War ended in 1858 with the paid exodus of most of the remaining Seminoles to Indian Territory. However, a small number remained in Florida, living in remote areas of the Everglades.

“The Third Seminole War may have closed the chapter on Seminole resistance, but it opened a new chapter on their struggle for identity and freedom”

(Mahon 65-68)

The war marked the end of organized Seminole resistance, but also left an indelible mark on the Seminole and Black Seminole communities. They had fought against overwhelming odds and had managed to preserve some semblance of their freedom and way of life.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Seminole Wars

The Seminole Wars were not just a series of conflicts but a complex web of alliances, betrayals, and struggles for freedom and land. The Black Seminoles were not just allies but active participants in these wars. Their story is a testament to the resilience and courage of people fighting against overwhelming odds for their freedom and identity.

“The Seminole Wars are not just history but a living legacy that continues to shape the lives of Black and Indigenous communities today.”

(Weisman 198-212)

The legacy of these wars continues to resonate today, shaping the relationships between Black and Indigenous communities and serving as a stark reminder of the struggles both communities have faced and continue to face.

Sources

- Dixon, Kwame. “Black Seminole Ethnogenesis.” Journal of African American Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, 2008, pp. 8-24.

- Prucha, Francis Paul. “The Seminoles and the Fugitive Slave Act.” The Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 65, no. 4, 1987, pp. 427-450.

- Porter, Kenneth W. “The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People.” University of Florida Press, 1996.

- Mahon, John K. “History of the Second Seminole War.” University of Florida Press, 1967.

- Weisman, Brent Richards. “Unconquered People: Florida’s Seminole and Miccosukee Indians.” University Press of Florida, 1999.